With so many priorities competing for their time, clinical laboratorians often must make deliberate, painful choices about which quality improvement (QI) projects offer the best return on scarce resources. Other times patient safety problems appear so quickly that they thwart careful plans for QI projects already in the queue. At our lab, such was the case with a QI project that tackled canceled specimens.

It started with several phone calls from clinicians about tests that had been canceled due to “specimen contamination” without further information. In some instances, the clinical team wanted the test results released for documentation even though they were clearly compromised by intravenous (IV) fluid, as was apparent by the number and pattern of abnormal test results. In other instances, we discovered that the lab had canceled test orders inappropriately: What initially appeared as a contaminated specimen represented accurate, but highly abnormal, test results for patients who were rapidly deteriorating. After investigating the issue, an array of problem cases surfaced, each more eye-opening than the last, revealing specimen contamination as a significant patient safety issue.

It became clear to us that clinical laboratory scientists should not be making unilateral decisions to cancel results for samples suspected of being contaminated. We needed a joint decision-making strategy that included both clinical laboratorians and healthcare providers to increase communication, documentation, and overall satisfaction for everyone involved in making these tough decisions.

Incorrectly canceling testing on a specimen that is not truly contaminated may lead to delayed results. Conversely, releasing erroneous, contaminated results could result in inappropriate diagnosis and treatment. Both scenarios have the potential to harm patients, leaving little room for doubt about our need for a multidisciplinary group of experts.

We started the QI project by asking the lab staff to simply print the screen of results in our laboratory information system (LIS) for the samples they believed were contaminated and for which they planned to cancel the test order per lab policy. This was a minor change to their workflow, but this data collection was critical to the project’s success.

After collecting and reviewing 3 months of data, we found that, on average, the lab suspected contamination in 125 specimens per month. Pathology residents audited the cancellations by perform-ing chart reviews.

The chart reviews revealed that some of the more seasoned clinical laboratory scientists were better at catching the less obviously contaminated specimens while the overtly contaminated specimens were accurately identified by both new and seasoned staff. The data also provided insight into who could benefit from targeted education. Overall, the data demonstrated that for 90% of the cancellations due to specimen contamination, clinical lab personnel had the same interpretation as the residents.

One of the goals defined early in the QI process was to increase the concordance rate between the behavior of the lab personnel and the clinical results collected by the residents. This led us to improve our test cancellation procedure by adding a section that highlights common contaminants, such as normal saline and heparin, and provides general examples of how they can affect lab results (1, 2). By providing more specific criteria for evaluating specimen contamination, we were able to help the lab staff more accurately identify suspicious samples.

Soliciting feedback following the procedural change yielded several ideas for additional educa-tional tools, including a notebook with examples of compromised patient test results to illustrate typical patterns. We also implemented safeguards such as encouraging staff to contact the resident on call or their medical director if they had questions about whether a sample is contaminated since, in general, lowering the threshold for escalating concerns improves patient safety.

Although it is important to properly identify a compromised sample to prevent treatment errors, it is equally as important to communicate clearly about any compromised sample. We updated our test cancellation procedure to provide guidance on how to communicate suspicion of specimen contamination to other sections within the lab as well as to patient care providers.

To improve communication internally, the clinical laboratory scientists must now query the LIS to take several required actions. These include: investigating other results on the same order that may be adversely affected; reviewing previous orders to see if there was a recent cancellation due to contamination and escalating to a medical director if warranted; determining if the patient specimen was collected in the inpatient setting; and notifying the phlebotomy supervisor if the contaminated specimen was collected in-house by a phlebotomist.

Having this information available prior to calling the clinical team means the lab often can make a single, more productive phone call. This procedure also helps the lab escalate problems more quickly through the appropriate channels.

We also recognized that clinicians need to know why the lab suspects sample contamination so that they can be involved in making the decision to cancel testing. Clinicians have specialized knowledge about the patient and their departmental practices, just as clinical laboratory scientists have specialized knowledge of the assays and instruments.

The new protocol requires clinical laboratory scientists to explain to the patient care provider why contamination is suspected based on the test results generated. They are also instructed to inquire about how the specimen was collected to determine if contamination is likely due to drawing through a peripheral IV catheter. If this investigation confirms that a sample has been contaminated, we can-cel the affected tests and re-draw the patient at the physician’s discretion.

We also require that staff use a new cancellation comment to document that the order was canceled specifically due to suspected contamination, including the clinician’s name who approved the cancellation. If the care provider cannot confirm or does not agree that contamination is likely, then we release the results with a comment documenting that the ordering physician was notified about the suspected specimen contamination and to repeat testing if clinically indicated. We also use this comment when a physician wants the contaminated results released into the medical record for documentation.

Gaining traction with this QI project was challenging but worth the effort. Ultimately, implementing the workflow changes described above improved communication both in and out of the lab, enhanced documentation of suspected contaminated results, and most importantly, improved patient safety.

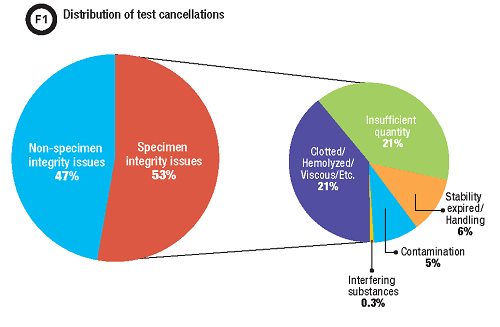

A post-intervention data review demonstrated that approximately 50% of our test cancellations were due to specimen integrity issues such as insufficient quantity for testing, hemolysis, or detection of an interfering substance (Figure 1). With the new cancellation comment, we identified that approximately 10% of these specimens were cancelled due to contamination. This translates to a total of 5% of all test cancellation in our lab for which the enhanced procedure improved communication and documentation, approximately 1,500 specimens a year.

This small QI victory provided the confidence and momentum needed to tackle larger issues with the same persistence. It also fostered better inter-departmental relationships with caregivers. Without these relationships, other QI initiatives down the road would not have been possible.

Jaime Noguez, PhD, DABCC, is the associate director of clinical chemistry and toxicology at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and assistant professor of pathology at Case Western Re-serve University in Cleveland, Ohio.